Last Thursday, I accompanied École Dirigeable on a school trip to Paris, where we visited the Galerie de Paléontologie et d’Anatomie Comparée and the Grande Galerie de l’Évolution at the Museum of Natural History. The trip had all the predictable pleasures of looking at dinosaurs and stuffed giraffes in the company of children: the childlike wonder with which the students admired the tail bones of an Apatosaurus; the childlike mischievousness with which students who had illicitly touched the taxidermied specimens sought to “contaminate” their classmates; and the all too adult anxiety with which the students fussed over their digital cameras. Between gallery visits we had a rainy picnic in the Jardin des Plantes and played What Time is it, Mr. Wolf?, churning up the gravel alleys under the horrified eyes of the paramilitary gardeners who consoled themselves by rigorously enforcing the prohibitions of walking on, placing bags on or even looking at the garden’s lawns. How did you say pelouse interdite in English, the small French children wanted to know, and I had to resist the temptation of offering them the unidiomatic calque of ‘forbidden lawn.’

At the end of the day, our return to Beauvais was delayed by a large demonstration directly in front of the Jardin des Plantes – linked to the day’s national strike in protest against the government’s proposed reform of the retirement system – which prevented our buses from returning on time to collect us. The small French children were very taken with the protest: “ah yes,” they said, matter-of-factly, “those are the fonctionnaires on strike.” As the wait dragged on, their attitude towards the strikers shifted from interest to unconscious emulation. “There’s no way I’m coming to school tomorrow,” more than one student declared, “It’s just ridiculous. I won’t be home until 11 PM, and then I’ll have to eat dinner, and I won’t be in bed before midnight. How could I possibly get up for class in the morning? Outrageous!”

***

Then again, perhaps the real reason I so enjoyed this trip to the museum was simply the joy which every overgrown child gets from looking at wild animals. On Sunday, I returned to Paris by myself to see a retrospective of husband-and-wife sculptors and furniture designers François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne at the Musée des Arts décoratifs. Animals and plants are the sole subject of the Lalannes’ whimsical oeuvres, and my visit to the exhibition was one of the most joyful hours I have ever spent in a museum. A wonderful spirit of magic realism suffuses many of the pieces on display, ranging from François Xavier’s larger-than-life sized sheet metal sculptures of minotaurs and hoofed rabbits, standing calmly on strips of Astroturf, to Claude’s cabbages with feet and miniatures of snails metamorphosing into human thumbs (although the exhibition is entitled Les Lalanne, the two artists rarely collaborated on individual pieces). François-Xavier’s work, in particular, blurs the line between sculpture and furniture to terrific comic effect: a hippopotamus whose belly opens up into a bathtub, and whose mouth becomes a sink; birds with lamps for tail feathers; a series of rhinoceroses which fold out into writing desks or disassemble into armchairs. Most magical of all, though, are his monumental, gimmick-less animal sculptures which blend realism with the irrepressible joy of plush toys and cartoons: a herd of bronze-and-wool sheep, on casters for easy realignment, or a pair of impossibly shaggy metal and wool camels, perched contentedly on their Plexiglas dunes.

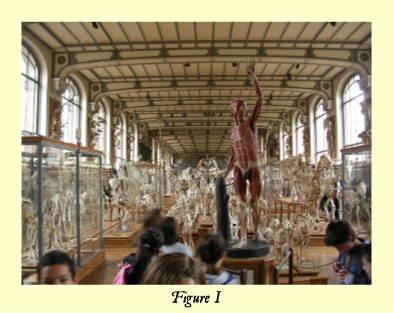

My policy of celebrating good weather with outdoor games of “What Time is it Mr. Wolf?,” honed during greyness of February and March, threatened to derail the entire English-language curriculum, a problem exacerbated by the ability of my charges to manipulate the game in order to both prolong it indefinitely and drain it of any educational value. At École Dirigeable, the students discovered that by taking miniscule steps forwards they could remain forever out of range of Messrs. Loup, while at École Rex the fastest runners in one class decided that the chase would be more exciting if they ran away from safety and taunted their chubbier pursuers. Inside, École Rex was transformed into a greenhouse, as classrooms, their red and yellow curtains vainly shut against the sun, heated and filled with a sweaty vapour, whose remarkable extent only became apparent when one stepped back into the Alpine coolness of the hallway. Students returned from recess panting, with glassy eyes and fevered cheeks, and wet out again rosier and damper than before. The miasma brought with it a predictable lethargy: during one sleepy afternoon review of the words for pizza toppings, a seven year-old, without any particular surprise or interest, looked at a pair of onions on a flashcard (Figure I) and remarked “ah, un

My policy of celebrating good weather with outdoor games of “What Time is it Mr. Wolf?,” honed during greyness of February and March, threatened to derail the entire English-language curriculum, a problem exacerbated by the ability of my charges to manipulate the game in order to both prolong it indefinitely and drain it of any educational value. At École Dirigeable, the students discovered that by taking miniscule steps forwards they could remain forever out of range of Messrs. Loup, while at École Rex the fastest runners in one class decided that the chase would be more exciting if they ran away from safety and taunted their chubbier pursuers. Inside, École Rex was transformed into a greenhouse, as classrooms, their red and yellow curtains vainly shut against the sun, heated and filled with a sweaty vapour, whose remarkable extent only became apparent when one stepped back into the Alpine coolness of the hallway. Students returned from recess panting, with glassy eyes and fevered cheeks, and wet out again rosier and damper than before. The miasma brought with it a predictable lethargy: during one sleepy afternoon review of the words for pizza toppings, a seven year-old, without any particular surprise or interest, looked at a pair of onions on a flashcard (Figure I) and remarked “ah, un